War and medicine by Quentin Smith

Does society benefit medically from war?

(Published in Todays Anaesthetist 2010 Vol 25)

Our ability to inflict bodily injury on our neighbours through violent acts of war arguably reveals human behaviour at its worst. Yet in direct contrast our desire to alleviate suffering, to help and to heal our fellow humans in perilous need demonstrates the very best of human endeavour. Can these opposite extremes possibly co-exist, and has our history of obsession with cruelty improved our ability to be kind?

In the Trojan War of 1200BC, Homer documented the mortality of war wounded at 77 percent, and he praised the role and efforts of war surgeons. Hippocrates wrote about the treatment of extremity injuries around 450BC, and with remarkable insight commented that war was the “surgeon’s best training ground”. Not surprisingly, therefore, the Romans became pretty good at treating their war wounded and built forward hospitals in every fort. An excellent example of this can be seen at Housesteads Fort, one of twelve permanent forts built in 124AD on Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland. As such the Romans are credited with establishing the very first military hospitals.

Galen was one of the best remembered of the Roman surgeons. By 200AD he had refined the use of sutures to treat wounds and even ventured into the field of muscle and nerve repairs. In the Middle Ages the use of bandages and techniques to stop bleeding became established, but there was still a very poor understanding of the reasons why so many injured soldiers died.

It was perhaps the introduction of gunpowder into Europe in the 1300’s that catapulted wound management into a new era. Gunpowder blasts and projectiles resulted in shattering injuries and contamination of wounds the likes of which had never before been encountered. Sepsis became a major problem and to combat it the use of widespread and early amputation was the only option available to surgeons. For about 250 years surgeons believed that gunshot wounds were intrinsically poisonous, and that the cornerstone of their management should involve cauterisation of the wound with burning oil.

Then in 1537 during the siege of Turin, a young French surgeon called Ambroise Pare ran out of cauterising oil. For some reason he did not order more oil but simply changed his management technique to that of selective wound cleansing, observing that the results were far better than cauterisation. He had unwittingly introduced the world to wound debridement, though it took him about thirty more years before he wrote openly about this experience.

Over the next 200 years or so surgeons remained pre-occupied with early and increasingly aggressive amputations to treat limb injuries. But still they wondered why their patients continued to die (some might unfairly suggest that little has changed). During the American Civil War of the 1860’s the first attempts to treat “wound shock” were recorded. Intensive nursing of wounded soldiers was introduced in the Crimean War and is credited with a dramatic improvement in hospital sanitation and consequent survival, thanks largely to Florence Nightingale.

During the Spanish American War of 1898 the administration of a salt solution either subcutaneously or by enema was used successfully to prolong life after blood loss. And so the infusion of fluid to correct haemorrhagic shock became established, and the transfusion of blood was widely used in WW1. The greatest problem in WW1 was the contamination of wounds with farm soil rich in animal manure. But despite the massive challenge of gangrene, widespread early prophylactic amputation was gradually replaced with debridement, antisepsis and delayed primary closure. WW1 also saw the introduction of triage into casualty management.

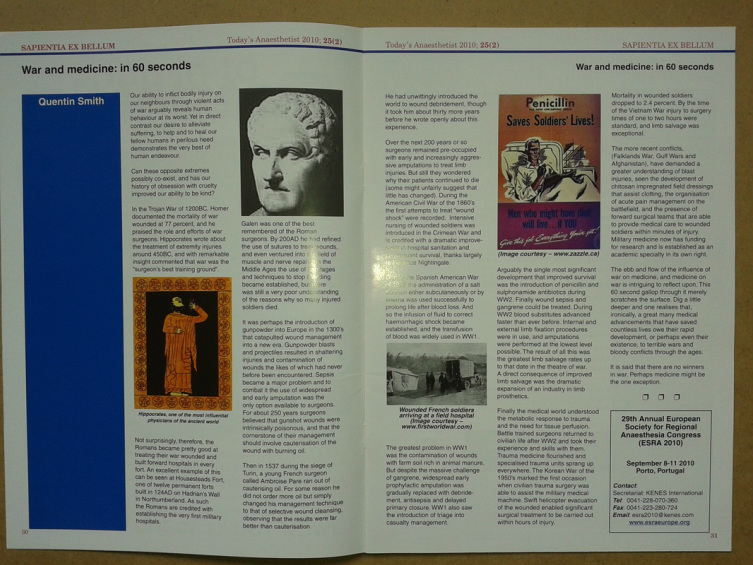

Arguably the single most significant development that improved survival was the introduction of penicillin and sulphonamide antibiotics during WW2. Finally wound sepsis and gangrene could be treated. During WW2 blood substitutes advanced faster than ever before. Internal and external limb fixation procedures were in use, and amputations were performed at the lowest level possible. The result of all this was the greatest limb salvage rates up to that date in the theatre of war. A direct consequence of improved limb salvage was the dramatic expansion of an industry in limb prosthetics.

Finally the medical world understood the metabolic response to trauma and the need for tissue perfusion. Battle trained surgeons returned to civilian life after WW2 and took their experience and skills with them. Trauma medicine flourished and specialised trauma units sprang up everywhere. The Korean War of the 1950’s marked the first occasion when civilian trauma surgery was able to assist the military medical machine. Swift helicopter evacuation of the wounded enabled significant surgical treatment to be carried out within hours of injury. Mortality in wounded soldiers dropped to 2.4 percent. By the time of the Vietnam War injury to surgery times of one to two hours were standard, and limb salvage was exceptional.

The more recent conflicts, (Falklands War, Gulf Wars and Afghanistan), have demanded a greater understanding of blast injuries, seen the development of chitosan impregnated field dressings that assist clotting, the organisation of acute pain management on the battlefield, and the presence of forward surgical teams that are able to provide medical care to wounded soldiers within minutes of injury. Military medicine now has funding for research and is established as an academic specialty in its own right.

The ebb and flow of the influence of war on medicine, and medicine on war is intriguing to reflect upon. This gallop through it merely scratches the surface. Dig a little deeper and one realises that, ironically, a great many medical advancements that have saved countless lives owe their rapid development, or perhaps even their existence, to terrible wars and bloody conflicts through the ages.

It is said that there are no winners in war. Perhaps medicine might be the one exception.

Does society benefit medically from war?

(Published in Todays Anaesthetist 2010 Vol 25)

Our ability to inflict bodily injury on our neighbours through violent acts of war arguably reveals human behaviour at its worst. Yet in direct contrast our desire to alleviate suffering, to help and to heal our fellow humans in perilous need demonstrates the very best of human endeavour. Can these opposite extremes possibly co-exist, and has our history of obsession with cruelty improved our ability to be kind?

In the Trojan War of 1200BC, Homer documented the mortality of war wounded at 77 percent, and he praised the role and efforts of war surgeons. Hippocrates wrote about the treatment of extremity injuries around 450BC, and with remarkable insight commented that war was the “surgeon’s best training ground”. Not surprisingly, therefore, the Romans became pretty good at treating their war wounded and built forward hospitals in every fort. An excellent example of this can be seen at Housesteads Fort, one of twelve permanent forts built in 124AD on Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland. As such the Romans are credited with establishing the very first military hospitals.

Galen was one of the best remembered of the Roman surgeons. By 200AD he had refined the use of sutures to treat wounds and even ventured into the field of muscle and nerve repairs. In the Middle Ages the use of bandages and techniques to stop bleeding became established, but there was still a very poor understanding of the reasons why so many injured soldiers died.

It was perhaps the introduction of gunpowder into Europe in the 1300’s that catapulted wound management into a new era. Gunpowder blasts and projectiles resulted in shattering injuries and contamination of wounds the likes of which had never before been encountered. Sepsis became a major problem and to combat it the use of widespread and early amputation was the only option available to surgeons. For about 250 years surgeons believed that gunshot wounds were intrinsically poisonous, and that the cornerstone of their management should involve cauterisation of the wound with burning oil.

Then in 1537 during the siege of Turin, a young French surgeon called Ambroise Pare ran out of cauterising oil. For some reason he did not order more oil but simply changed his management technique to that of selective wound cleansing, observing that the results were far better than cauterisation. He had unwittingly introduced the world to wound debridement, though it took him about thirty more years before he wrote openly about this experience.

Over the next 200 years or so surgeons remained pre-occupied with early and increasingly aggressive amputations to treat limb injuries. But still they wondered why their patients continued to die (some might unfairly suggest that little has changed). During the American Civil War of the 1860’s the first attempts to treat “wound shock” were recorded. Intensive nursing of wounded soldiers was introduced in the Crimean War and is credited with a dramatic improvement in hospital sanitation and consequent survival, thanks largely to Florence Nightingale.

During the Spanish American War of 1898 the administration of a salt solution either subcutaneously or by enema was used successfully to prolong life after blood loss. And so the infusion of fluid to correct haemorrhagic shock became established, and the transfusion of blood was widely used in WW1. The greatest problem in WW1 was the contamination of wounds with farm soil rich in animal manure. But despite the massive challenge of gangrene, widespread early prophylactic amputation was gradually replaced with debridement, antisepsis and delayed primary closure. WW1 also saw the introduction of triage into casualty management.

Arguably the single most significant development that improved survival was the introduction of penicillin and sulphonamide antibiotics during WW2. Finally wound sepsis and gangrene could be treated. During WW2 blood substitutes advanced faster than ever before. Internal and external limb fixation procedures were in use, and amputations were performed at the lowest level possible. The result of all this was the greatest limb salvage rates up to that date in the theatre of war. A direct consequence of improved limb salvage was the dramatic expansion of an industry in limb prosthetics.

Finally the medical world understood the metabolic response to trauma and the need for tissue perfusion. Battle trained surgeons returned to civilian life after WW2 and took their experience and skills with them. Trauma medicine flourished and specialised trauma units sprang up everywhere. The Korean War of the 1950’s marked the first occasion when civilian trauma surgery was able to assist the military medical machine. Swift helicopter evacuation of the wounded enabled significant surgical treatment to be carried out within hours of injury. Mortality in wounded soldiers dropped to 2.4 percent. By the time of the Vietnam War injury to surgery times of one to two hours were standard, and limb salvage was exceptional.

The more recent conflicts, (Falklands War, Gulf Wars and Afghanistan), have demanded a greater understanding of blast injuries, seen the development of chitosan impregnated field dressings that assist clotting, the organisation of acute pain management on the battlefield, and the presence of forward surgical teams that are able to provide medical care to wounded soldiers within minutes of injury. Military medicine now has funding for research and is established as an academic specialty in its own right.

The ebb and flow of the influence of war on medicine, and medicine on war is intriguing to reflect upon. This gallop through it merely scratches the surface. Dig a little deeper and one realises that, ironically, a great many medical advancements that have saved countless lives owe their rapid development, or perhaps even their existence, to terrible wars and bloody conflicts through the ages.

It is said that there are no winners in war. Perhaps medicine might be the one exception.